The walls were closing in on Judge Little.

For years, even before Gary Little reached the King County Superior Court bench, there were rumors he took unusual interest in young boys. Little would frequently request 1-on-1 meetings with juvenile defendants in his judicial chambers, and some said he kept in contact with defendants even after they’d cycled out of the legal system. Multiple teenagers alleged that Little had invited them to visit him at his home on Sinclair Island in the San Juans.

But, the Washington Post reported at the time, even after a now-sealed internal investigation resulted in Little being moved out of juvenile court, he filed for re-election. His challenger publicized the allegations, and after years of silence on the matter, KING-TV ran a piece that described Judge Little taking a 14-year-old juvenile defendant out shopping for a Christmas card for the boy’s father. Immediately after the piece aired, Little announced he would not seek re-election, and would leave the bench at the end of the year.

But more allegations followed, claiming that Little had sexually assaulted three students at Lakeside High School when he taught a pre-law class there. Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter Duff Wilson reportedly called Judge Little to let him know the paper would be running a story on these accusations the following day.

That night, August 18, 1988, Judge Little committed suicide in his judicial chambers on the eighth floor of the King County Courthouse in downtown Seattle.

A janitor found his body. In a note next to the .38 caliber gun he used, Judge Little had written, in part: “I have chosen to take my life. It's an appropriate end to the present situation. I had hoped that my decision to withdraw from the election and leave public life would have closed the matter. Apparently these steps are not satisfactory to those who feel more is required, so be it.”

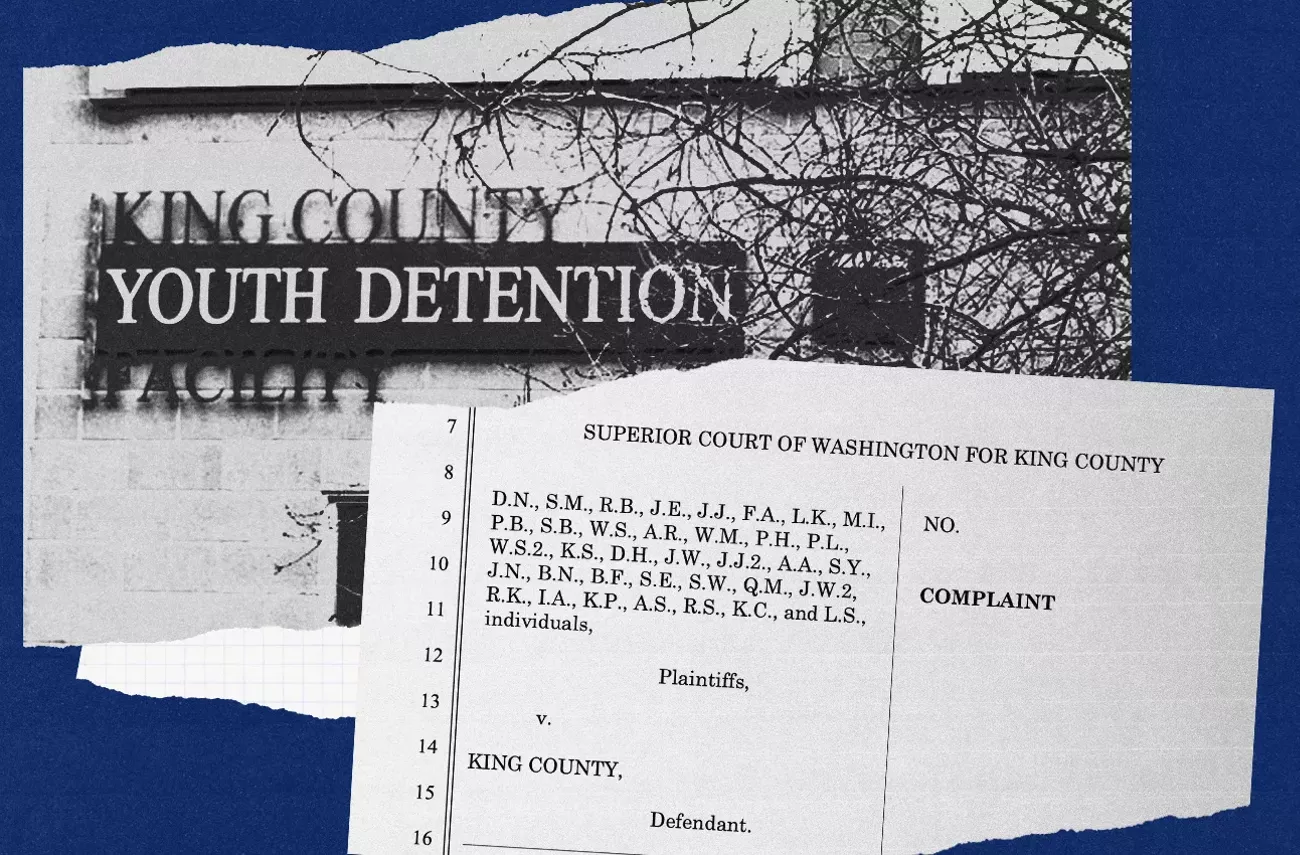

But the matter is not closed for 36 former juvenile defendants who, in a lawsuit filed yesterday against King County, allege that the County failed to protect them from sexual abuses from the 1960’s through the 2000’s, at the hands of Little and 37 other authority figures.

The 36 complainants are suing the County for negligence, claiming that their assaults were “an institutional failure caused by and maintained through King County’s willful disregard for the well-being and safety of some of the most vulnerable children in the State of Washington.”

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for King County said: "We will be thoroughly investigating each claim. We are committed to the safety and well-being of all youth in our juvenile detention facility. We will continue to uphold robust standards that have been put in place over the course of many years to protect young people in our care from harm."

One-on-One

Justin Reed Early was just 10 years old when he met Judge Gary Little, according to the complaint. It was 1980, and Early, who appears as J.E. in the complaint, says he had lived a hard life already, leaving home to avoid further abuse from his father, who was “a violent raging alcoholic,” he told The Stranger in an interview. He’d fallen in with other street kids, sleeping on a spare cot whenever he could, and hustling to make money. When he was picked up for prostitution and appeared in Judge Little’s court, he says, he was surprised at Little’s friendliness.

The complaint states that “he was immediately targeted by the assigned judge, who worked with King County staff to have [Early] and other youth escorted to his chambers for improper one-on-one time.”

“I remember when he told the public defender after a court hearing that he'd like to see me in his chambers,” Early, now in his 50’s, told The Stranger. “The public defender who was with me was ready to go with me into the chambers, and he said, ‘No, no, no, just him.’”

“It made me feel special,” Early says. “It made me feel like I was cared about, right? So there was a certain element about it that was positive for me. But I realized after spending at least a little bit of time on the streets that there were ulterior motives here. I could tell that he was grooming me. He touched me gently on my shoulder and my arms. He was just very, very gentle. I could tell that something was up. I wasn't an idiot, you know?”

According to the complaint, in those judicial chambers, during those private meetings, Judge Little eventually “made over-the-clothing sexual contact with J.E’s genitals.”

“The abuse continued after J.E.’s release,” the complaint says.

“He came and took me on a pass from the homeless shelter more than once,” Early told The Stranger. “He came and signed me out, took me to lunch, and let me sit on his lap and drive his car while he played with me.”

Early says the abuse continued for years, with Little giving Early small amounts of money for sexual favors. “If I needed money to eat, I knew I could go to him,” Early says. “I went to his condo in downtown Seattle. He lived in a high rise. I knew where he lived. I went there several times when I was desperate. And I could tell he was really uncomfortable that I was at his house because I was his dirty little street kid.”

Judge Little even offered to buy Justin’s silence and “promised to pay for college if he didn’t report him,” the complaint states. “Nevertheless, J.E. reported the abuse to a county contractor… This contractor failed to escalate J.E.’s report.”

Meanwhile, according to the complaint, Judge Little was targeting new victims. A plaintiff identified in the suit as J.J. says in the 1980’s, in open court, Judge Little offered to reduce the 15-year-old’s sentencing if J.J. came over to his house and performed chores for him.

King County permitted Little to remove J.J. from detention and take him to his home, the complaint says, at which time Little sexually abused J.J.

The Pizza Man

The lawsuit doesn’t just accuse Judge Little. It alleges that King County’s negligence allowed these young people to be victimized by fellow inmates, guards, nurses, and even teachers.

Memory issues are common among sexual abuse survivors. Multiple plaintiffs mentioned that they’ve experienced blocked memories as a result of their trauma, not to mention the issue of passing of time: some of these memories are now 50 years old. The names of these offenders, as identified by the plaintiffs in this case, are as best they can recall these decades later, and some are known only by their nicknames, like “Crazy Kwame” or “Snake Eyes.”

But four plaintiffs described a guard known as “the pizza man,” a large, white, brown-haired man who at the time, in the early 1980’s, wore his curly hair long with a beard to match. Each used similar physical descriptions.

Ralph Bell, who’s referred to as R.B. in the complaint, was only 13 years old when he was picked up along with some friends for auto theft, he told The Stranger. They’d found a Camaro in a car lot with the keys inside and drove it around for a joy ride. But once he reached the juvenile detention center, for Ralph, he met a guard that was welcoming.

“He was very friendly and engaging, like a camp counselor,” Ralph says.

“It began with [the guard] explaining he could help R.B. with leg cramping from sports by giving him massages,” the complaint states, “then escalated to sexual contact over and under the clothes with R.B.’s penis and testicles and sexual contact by [the guard]’s mouth with R.B.’s penis.”

Ralph told The Stranger that the guard had him roll over and masturbated him to orgasm, licking his ejaculate off his hand afterward.

“It really kind of grossed me out and made me feel really weird. Then he talked to me for a minute and then he left and locked me in the cell,” Ralph says. “Of course he came back the next night.”

“He could come in the night, anytime he wanted to, open the door, and come in and [sit] between me and freedom where I couldn't get loose,” Ralph continues. “I couldn't get away from this guy. He had the key. And there was nothing I could do about that.”

When he left, the complaint states, the guard tried to give Ralph his phone number.

Another plaintiff, identified in the complaint as S.M., had a much longer experience with this County employee. At 15 years old, he and a friend started a fire at Federal Way High School and got picked up for arson.

“And that's when my whole life changed,” S.M. says, who asked that we not use their full name, for their privacy.

In the complaint, S.M. alleges it started with the guard “bringing pizzas to certain boys to share in the dayroom during his shift. [The guard] then began spending unnecessary one-on-one time with S.M. in his cell.”

“It's almost like being hypnotized, you know?” S.M. says. “I don't know what other way to say it.”

The complaint alleges that the “abuse escalated to include sexual contact with S.M.’s penis, forcing S.M. to taste [the guard]’s semen, and making sexual contact between his mouth and S.M.’s penis.”

Then after S.M. was released, according to the complaint, the guard “continued to abuse him by using the personal information King County kept on detainees to locate him outside the facility.”

“He convinced my parents that he was like the big brother I needed, and had all this guidance, you know. [I was] somebody to take under his wing,” S.M. says. In an interview with The Stranger, he alleges the two would drive back to the guard’s apartment and engage in sexual acts.

The trauma of this experience left S.M. with a few images burned into his mind. “I can tell you what he wore,” S.M. tells The Stranger. “I can tell you what he drove, where he lived, everything…I mean, you just don't forget things like that.”

The Cost of Silence

In 1989, the Commission on Washington Courts issued a report on judicial elections and discipline. Just a year after Judge Little’s suicide, they leaned on the example heavily as a warning for future judicial conduct.

The report criticized the Commission on Judicial Conduct’s response to years of complaints about Little, saying, “the CJC undertook only minimal follow up, and that at a slow pace.” The report said this behavior demands intense scrutiny because of the possibility that it results in “potentially devastating consequences.”

The plaintiffs in this lawsuit expressed the profound effects this abuse had on their lives, and their hope that although this might not provide closure, it might prevent future abuse.

Early, the former street kid who says he was abused by Little at 10 years old, is still searching for normalcy in his 50’s. “I don't have normal relationships,” he says. “I'm single. I probably won't ever be in a relationship. There's just certain things that have traumatized me to the point where I can't live a normal life.”

“It affects you in ways that you don't actually expect it to,” Ralph says, now 59. “I just disintegrated. I fell off in school, which I really used to enjoy. And I got in trouble after that. I never got in trouble before that. But then after that, I did. I started drinking. I got in quite a few fights.”

But then he found salvation—or something like it—in an unlikely place.

“I started roller skating,” he says. “Maybe that's besides the point, but I started doing that. I got really good at it. And that helped a lot. I quit fighting so much.”

“You get this anger,” S.M. says. “At first you get this anger inside, you know. And then you…well, you continue to have anger for a long time. And that's just not the personality that I had or who I would have been if this had not happened to me. And I felt that they knew what was going on in King County. And, in effect, they allowed it.”

S.M. says he only recently told his family what happened, but he feels like over the decades—maybe because he held it in so long—he’s developed a sixth sense to identify similarly abused people.

“There's been times I've recognized people I don't even know, just recognized they're going through what I went through. And I'll approach them. I’ve done that,” S.M. says. “How a person interacts with another person, you know. How they look at them, how they talk to them…it's like a sense. You sense it.”

He says it happens all the time.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to include comment from King County.