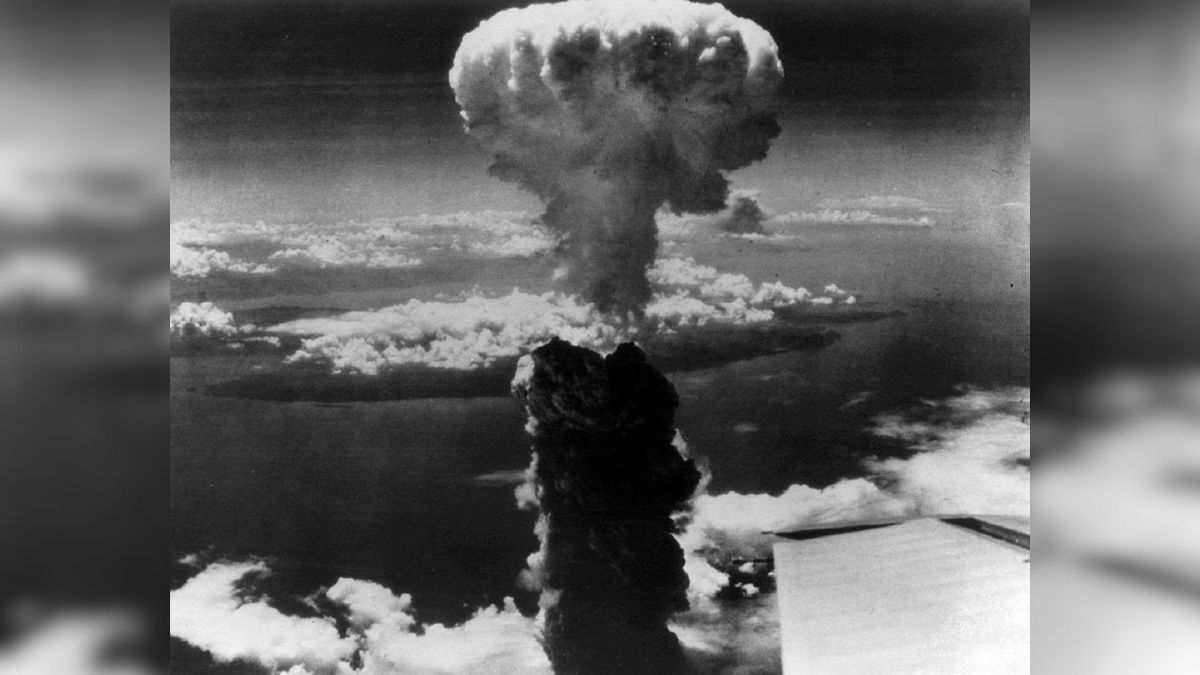

Cross-border tensions between India and Pakistan have climbed to new heights. Amid escalating military operations, the world is once again confronted with a harrowing question: what happens if Pakistan launches a nuclear missile?

The issue transcends conventional warfare. It enters a domain where the margin for error is non-existent, where every strategic calculation hinges on the doctrine of deterrence and where the consequence of miscalculation is unthinkable devastation.

Pakistan’s nuclear programme, born from its perception of existential threat following India’s 1974 nuclear test , has matured into a formidable deterrent.

Since the April 22 terror attack in Pahalgam and retaliatory measures by India that followed, politicians in Pakistan have made explosive threats mentioning nuclear weapons. Pakistani minister Hanif Abbasi remarked last month , “We have kept Ghori, Shaheen, Ghaznavi, and 130 nuclear weapons only for India.”

Pakistan’s Defence Minister Khawaja Asif, in an interview with Reuters has also said that Pakistan would only use its arsenal of nuclear weapons if ”there is a direct threat to our existence”.

On Saturday (May 10, 2025), Pakistan PM Shebaz Sharif reportedly called a meeting of the National Command Authority, the apex body overseeing the nation’s nuclear arsenal, a meeting which Asif has now claimed never happened .

“No meeting has happened of the National Command Authority, nor is any such meeting scheduled,” Asif told Karachi-based ARY TV.

How Pakistan is nuclear-capable

Over the past two decades, Islamabad has developed a diverse array of nuclear-capable delivery systems spanning land, air and sea. The Shaheen-II missile, with a range of approximately 2,000 kilometres, is central to Pakistan’s land-based nuclear posture.

More recently, the Ababeel missile, equipped with Multiple Independently targetable Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs) signals a significant leap in Pakistan’s ability to overwhelm enemy defences.

On the air front, Pakistan’s fleet of F-16s and Mirage aircraft are believed to be capable of deploying nuclear gravity bombs and air-launched cruise missiles such as the Ra’ad, with a range exceeding 350 kilometres.

Meanwhile, the Babur-3 submarine-launched cruise missile represents a developing but ambitious bid for a second-strike capability — vital for maintaining credible deterrence in the event of a first strike disabling land-based assets.

According to the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), Pakistan has upwards of 170 nuclear warheads compared to India’s 180, as of 2025.

How India may be able to defend itself

India, on the other hand, has adopted a declared “No First Use” policy since the early 2000s and has developed a strategic nuclear triad to enforce this doctrine.

Its arsenal includes land-based Agni series missiles, capable of reaching targets from neighbouring states to as far as China, nuclear-capable aircraft like the Mirage 2000 and Jaguar, and most crucially, submarine-based ballistic missile platforms like the INS Arihant and INS Arighaat.

These nuclear-powered submarines give New Delhi a stealthy, survivable second-strike option, reinforcing its deterrence posture.

Missile defence remains one of the most intensely debated aspects of modern military planning in the subcontinent.

While India has made major strides in developing a layered Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) shield, comprising systems like the Prithvi Air Defence (PAD) and the Advanced Air Defence (AAD) interceptors, the task of successfully detecting and destroying an incoming nuclear missile is far from assured.

At speeds that can exceed 24,000 kilometres per hour and with decoy or MIRV capabilities, even a single missile can render defence systems ineffective.

The Swordfish radar system, designed to track enemy projectiles up to 1,500 kilometres away, is part of India’s response to this challenge.

Yet, military experts consistently highlight the point that no missile shield guarantees complete protection against a nuclear salvo, particularly one involving multiple warheads.

What MAD entails

This brings the discourse back to the enduring concept of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) — a principle that has, paradoxically, helped preserve peace among nuclear powers. MAD rests on the assumption that no rational actor would initiate a nuclear strike knowing that it would inevitably trigger a retaliatory response resulting in total annihilation.

The doctrine works as a deterrent because the destruction would be so catastrophic for both the attacker and the defender that neither would benefit. In the India–Pakistan context, this logic still holds.

Both nations possess second-strike capabilities and understand that a nuclear war, regardless of who launches first, would result in national collapse, mass civilian casualties and a geopolitical fallout that would reverberate globally.

Why MAD is not foolproof

Nevertheless, MAD is not a foolproof safety net. The threat lies not in official doctrines, which are usually shaped with extreme caution, but in the possibility of misinterpretation, rogue actors or unintended escalation during conventional conflicts.

Unlike the Cold War standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union, where strategic communication channels were institutionalised and borders were not shared, India and Pakistan are separated by a tense and highly volatile Line of Control.

When fighter jets are engaged in combat, missiles are being fired at military installations and nationalist rhetoric escalates, the room for error narrows.

Moreover, Pakistan’s development of tactical nuclear weapons — smaller-yield warheads designed for battlefield use — further complicates the deterrence equation.

These weapons lower the nuclear threshold and risk normalising their use in conventional scenarios. India’s military doctrine, in contrast, states that any nuclear strike — tactical or strategic — will invite massive retaliation.

The real cost

All of this unfolds in a region where the civilian population is most vulnerable. Both countries host massive populations in densely populated urban centres.

A single nuclear detonation in cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Karachi or Lahore could result in hundreds of thousands of immediate casualties, with many more dying from radiation exposure and long-term fallout.

Hospitals, infrastructure, food supply chains and governance systems would collapse in the wake of such a catastrophe. International aid would struggle to respond, and the region would face ecological and economic consequences lasting decades.

Both India and Pakistan possess the means to destroy each other — and themselves.

As tensions flare and military manoeuvres dominate headlines, it is this restraint — this enduring understanding of the true cost of nuclear war — that remains South Asia’s most important line of defence.

As Pakistani politicians continue to invoke nuclear threats and Pakistan continues to escalate this conflict, the underlying message from Islamabad is clear: the nuclear option, while not a first choice, is not off the table.

Also Watch:

With inputs from agencies

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)