In September 2007, a backhoe uncovered a mass grave while excavating what had once been the exercise yard of the former Toronto Don Jail. A total of 15 bodies were discovered — the remains of inmates hanged on the prison’s gallows between 1872 and 1930.

Their stories are explored in “The Way of Transgressors” (Tidewater Press). Author Edward Brown used research and documents as the foundation for his portrayal of the condemned lives, and then drew on creative inspiration to bring the deeds of the past to vivid life.

Among the remains unearthed that day were those of George Dickson, also known as George Bennett. Dickson, a former employee at the Globe newspaper, killed the paper’s founder George Brown, a Father of Confederation, in 1880. Yet historical material on Dickson’s life is scarce. In researching the book, the author found that following Dickson’s execution, his siblings slightly changed their surname and relocated to the United States. Today, when informed of Dickson’s notoriety, descendants living in California are surprised to discover their familial connection to a murderer.

This excerpt is from a story titled “Remember Me.”

The book launch for “The Way of Transgressors” is Saturday, June 7 at 4 p.m. at Noonan’s Pub, 141 Danforth Ave.

Ten minutes after the drop, George Bennett — alias George Dickson — was pronounced dead and his body cut down. Prone on the gravel in the exercise yard, Bennett’s body, its ankles and wrists pinioned, was heaved onto a flimsy cart and wheeled inside the facility. A black flag was hoisted up the jail flagpole. The hangman removed the canvas mask required to conceal his identity, scratched his coarse cheeks.

Officials dispersed. Inmates dismantled the scaffold. A chatter of newspapermen departed. Outside the prison, the festive throng of spectators thinned. A small crowd lingered by the Don Bridge, shaded by a copse of black locust trees.

The hangman drew a small, hardback book from inside his jacket and made notations with a dull pencil. Gathering the half-inch soaped rope into a butterfly coil, he untied the noose and placed the rope into a sack. He stood a moment and gazed into the gauzy white face of the rising sun. At the base of the wall behind him, the inmate assigned to dig Bennett’s grave went at the earth with pick and shovel, quietly humming “It Is Well with My Soul.”

Before retiring to an unadorned apartment inside the jail where he had slept the previous night, the hangman collected his 40-dollar fee from Governor Green. Undressing, he leaned over a wash basin, splashed warm water on his face. He lathered shaving soap in a mug and shaved his cheeks smooth. Changing into a new black suit, he gulped from a flask. Sitting heavily on the stained mattress, the hangman unfolded a penny knife and cut lengths of rope from the cord that had recently launched Bennett into eternity. Placing personal effects into a carpetbag patterned with rosebuds, he lay back on the cot and catnapped.

An inquest was held pro forma in the small, black-and-white tiled prison hospital, austere as an anchorite’s cell. Thirteen jurors were selected. Bennett’s corpse was displayed on a table.

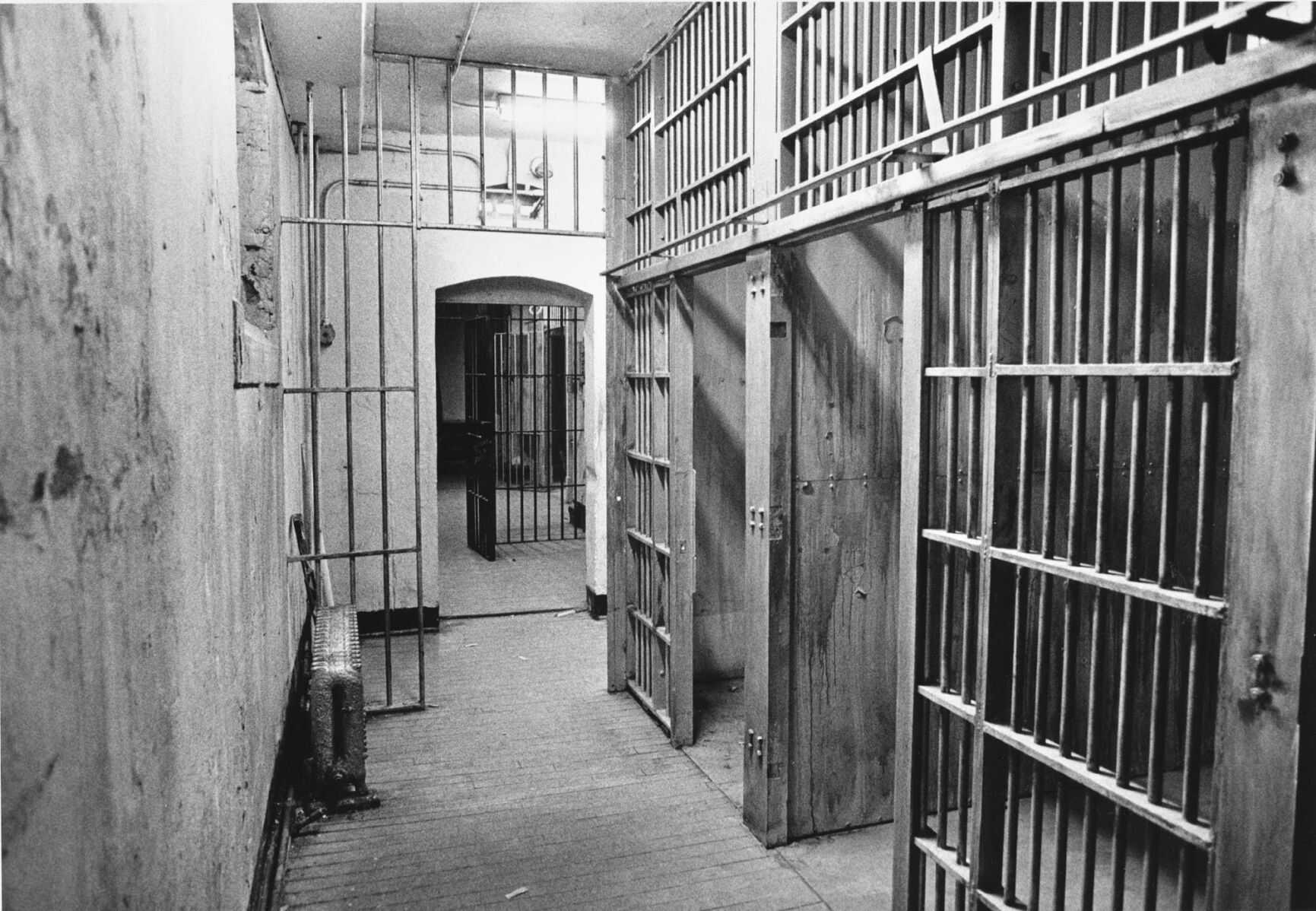

Looking up at rhe former site of the gallows, as seen in the Don Jail in 1987. The viewing platform is seen at the right top corner.

Reg Innell/Toronto Star file photoThe black sack covering the condemned man’s head was removed. The cord used to tie his wrists and ankles was cut and the corpse stripped of clothing. Five feet, two inches, Bennett was below medium height and weighed one hundred twenty-six pounds. He wore a black Van Dyke beard.

Between purplish lips, his tongue protruded, a black wedge of meat. His eyes were closed. His nose appeared to have been recently broken. Livid contusions marked his neck. His hands were a shade of blue similar to a morpho butterfly. The autopsy revealed congestion in the brain, lungs, and heart. The posterior ligaments of his upper vertebrae were separated.

As a result of the drop, his spinal column had dislocated. Medical examiner’s conclusion: death was instantaneous. The jury’s verdict, unanimous: the condemned had experienced no pain.

It was forenoon when the hangman approached the crowd lingering by the locust trees, rope sack, and carpetbag slung over his shoulder. In his free hand he held up samples of rope, repeating, “Souvenir? Souvenir. Justice is done. The righteous rejoice. The Honourable George Brown’s killer, finished by this rope. An historic day. A souvenir?”

Horse blankets spread on the ground, a rank stench fouled the air as families fried carp livers, potatoes, and bay mussels on naphtha stoves, breakfasting in the fashion of a picnic.

The crowd surrounded the hangman. Boys climbed out of trees. Men in blue and white check vests and felt derbies ambled toward him, rubbing their bellies and inhaling deeply from hooked ceramic smoking pipes.

An emaciated teenage boy with a harelip and rags for clothing dangled from a tree limb kicking his spindly legs. In a voice like bone pressed to an emery wheel, he recited a Bible verse about the powers of darkness, shouting at the executioner, “What’s it feel like killing for a living?”

The hangman’s expression remained flat. Indecipherable. A weathered tombstone. “Tell me your name, boy,” he shouted. Perched above the crowd, the slender boy repeated, “What’s it feel like killing for a living?”

The killer George Bennett, alias George Dickson, who killed Globe newspaper founder George Brown.

Nick Burton illustration“Well, if you must know, it feels like a full stomach and a clean suit of clothing. It feels like the taste of costly bourbon.” His nostrils flared. “It feels like a close shave and like the scent of a perfumed lady.”

Locking eyes with the crowd, he concluded, “It feels like a downy pillow at close of day.” He clasped his hands and mocked, “At least from my end of the rope, anyway.”

The hushed crowd erupted in laughter. The raw-boned boy appeared to shrink sizes. “Now,” the hangman taunted, “tell me, what’s the feel of hunger? How does it feel to have the face of a praying mantis? Tell me, what’s it feel like to be insignificant?”

A woman seated with her back to a wagon wheel leaped to her feet, beckoned the hangman, and snatched a sample of rope. Strands of auburn hair came loose from her chignon. Her cheeks flushed as she clenched the fibrous twine, shoving it toward her husband. Face set in a moue, she sulked, “This is foul. I want it.”

Her man paid with money from his purse.

After the hanging, Governor Green took breakfast. He instructed the chief turnkey to assign two inmates to prepare Bennett for burial, dressing the cadaver in clothing delivered the previous afternoon by Bennett’s three siblings, Patience, William, and Julie, as well as a flaxen-haired gentleman in a waistcoat, striped trousers and Christy stiff hat also named William.

Death cells, once for those awaiting execution, in Toronto’s Don Jail, as seen in 1987.

Reg Innell/Toronto Star file photoThis second William went by Billy. Patience, tall, comely, and darkly complected, had tugged the bell pull. William, a painter by trade, gripped a parcel of clothing wrapped in red butcher paper to his chest with whitewash-stained hands. Julie, the baby of the family, shaded herself under a parasol.

Carved into the alabaster keystone above the portico, the terrifying likeness of Cronos, the father of time, gazed into a blank future. Bald-faced hornets swarmed at the papery opening of a grey nest constructed in the architrave.

Following at least a dozen pulls, a turnkey with a tragic expression opened the heavy door.

“What?”

Patience murmured, “We’re here to visit our brother.”

Staring at them like they were zoo animals, he asked, “And?”

“And?” Patience cast a quick glance over her shoulder. “Allow us entry, please.”

The turnkey studied Patience with agitation, suspicion. The intense midafternoon sunlight made everything appear increasingly queer.

“Who’s your brother, then?”

“George Dickson,” Patience said, before correcting herself. “Bennett, George Bennett.”

“Bennett or Dickson? Which?”

“Bennett.”

Their father was of West Indian origin but, unlike his brother and two sisters, Bennett took after their mother in appearance.

The turnkey was indignant. “Bennett? The white man?”

Patience unfolded the pass Sheriff Jarvis had provided that granted permission to visit their brother in the death cell. The turnkey scrutinized the paper as sounds of carpentry, hammering, and sawing came from the rear of the jail. Swatting at a wasp, Julie lost her balance, nearly toppling down the limestone steps. William reached for his younger sister’s elbow. He dropped the parcel. The contents spilled out.

The turnkey looked past Patience to Billy. “Can you vouch for the woman?” Billy’s Adam’s apple rose and fell before he said, “The woman is my wife.”

The door creaked closed. While they waited, a wasp stung Julie on the cheek. The white-hot sting brought tears. Helping their sister to sit on the steps, they comforted Julie.

Minutes lapsed before the turnkey reappeared. In a mordacious tone he snarled, “No.”

“No? No, what?” Patience inquired.

“No visit,” he smirked. “Not today.”

“When? Tomorrow our brother —”

Julie pawed at her neckline. “My throat. I can’t —”

“The Way of Transgressors”

Edward Brown

Tidewater Press

282 pages

$24.95

Courtesy of Edward BrownWilliam removed the gold pin engraved with her initials from the collar of her shirtwaist and dropped it on the step. Billy rubbed the back of her hand and attempted to settle her, repeating, “Sh, sh. It’s OK. It’s OK.”

“I don’t understand,” Patience pleaded, holding up Sheriff Jarvis’s pass. “We’re permitted.”

Julie panted, gasped, “Breathing. Difficult.”

The turnkey uttered, “He wants visits from none of you. Bennett’s words, not mine.” The heavy door closed tight as a fist.

Jowls swollen, Julie clawed her throat, wheezing, “I can’t breathe —”

Face pressed against the closed door, Patience pleaded, “Please. Please. At the very least, help my baby sister. She’s only fourteen.”

Julie’s face and lips swelled terribly. A mud salve did not bring relief. Pleading to be rid of the pain, Julie moaned as they started for the emergency hospital. In their haste, Julie’s collar pin was included in the parcel of clothing assembled into a neat pile and left on the steps.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation